Sunday, October 10, 2021

1.

|

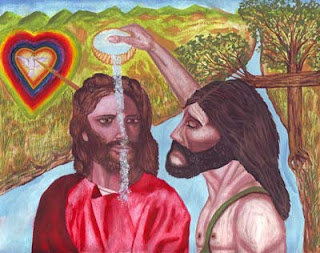

| Baptism, Ivaka Demchuk |

Together, they arrive at something like a crossroads, something like a confessional moment. John preaching repentance. And Jesus surrendering to the river, to the power of God in his life, to love divine. And so it is that this confessional moment invites imagination. This confessional moment acknowledges the hidden but potent promise of grace. This confessional moment finds the two of them knee-deep in the river. Together.

Now they say confession is good for the soul. And there’s some truth to that. I confess that I ate the last scoop of Ben & Jerry’s in the freezer. I confess that I lost last week’s salary on a bad bet in the Patriots’ game. I confess to a friend that I lied about something important. Confession can work that way.

But it’s more than self-improvement, right? It’s more than relieving the burden of a guilty conscience. Confession is a practice that sees possibility and potential in our brokenness. At least that’s our tradition; that’s our practice here. Confession is a practice that leans into reflection and renewal in seasons of despair. Confession is the beginning of repentance. And repentance is our turning again and then again and again toward the light.

I think that’s what Jesus is doing out there in the wilderness, knee-deep in the Jordan. I think he’s done with the politics of complaint and the spirituality of despair. I think he’s reached the end of whatever rope he’s been pulling on. And I think he’s ready to confess all the love in his spirit, and all the pain in his heart, and all the ways he can’t do what he’s got to do alone. This is the first step of his gospel journey.

And I wonder if it isn’t our calling as his disciples, our vocation as his siblings, our first step as the church. To confess our fears and folly. To see possibility and potential in brokenness. To surrender to the river. This is where the energy comes from. When we confess. This is where the light shines. When we confess. All the love in our spirits. All the pain in our hearts. And all the ways we can’t do what we’ve got to do alone. We just can’t.

2.

There was a story in the news this week—Martin told me about it—about an elderly Maine man who was taken to the hospital for a fairly routine procedure. He was beloved by his family, a wise soul in his community; and in the hospital he was attended to by a nurse who had refused her COVID vaccination. For whatever reason. He was infected there, the elderly man, in the hospital, by his nurse; and he died later that week. Leaving behind a family, a whole community, to wonder why we’re doing this to one another.

Now it’s so important to say right here is that health care workers—nurses, therapists, physicians and all the rest—health care workers have been brave and faithful throughout this pandemic. Risking and in many cases sacrificing their own lives and futures to tend to our illnesses and loneliness. Several of them among us today. We know this. So this story is an outlier in so many ways. It’s not about nurses, that’s for sure.

But there’s something dreadfully wrong with the spirit, the soul, the politics of our country—when we give in to conspiracy theories that have no credibility, when we insist on a kind of freedom which isn’t freedom at all, and when we deliberately and (let’s face it) consciously put one another at risk. I dare say, friends, it’s a confessional moment: a moment for confession and, in the spirit of the wild man Baptist, repentance. It’s time that we wrestle with the true meaning of freedom. It’s time that we celebrate the responsibilities that freedom confers. It’s time for confession.

3.

Which brings us to the wilderness.

John the Baptist appears in the wilderness: because the wilderness is where God’s people go to discern the ways of freedom, the practices that make us truly free. Geography matters in the biblical tradition. It was in the wilderness, we remember, that God instructed and coaxed a people in flight, and then (in that same wilderness) disciplined and tested and loved that fledgling community, into new patterns of sabbath faithfulness, into new practices of covenant and compassion, into new courage for liberation and freedom. Israel. The word means the people who wrestle with God. Israel. It was in the wilderness that so many prophets opened their minds and hearts to new visions of wholeness and communion. Insisting that we wrestle with God and embrace God’s freedom together. Not some FOX-news version of freedom. Not some angry, gun-toting, neighbor-hating version of freedom. But God’s freedom. God’s freedom. Freedom for one another.

“Repent!” This is John, in the wilderness. “Repent! Turn yourselves in a different direction. Face God’s promise together. Repent!” John doesn’t show up in the well-manicured precincts of the Jerusalem temple. He doesn’t arrive on time for a preaching gig in a well-established pulpit. He appears in a liminal space, in the wilderness, locusts spilling out of his pockets and wild honey on his fingertips. Even his appetite is edgy.

And we know—because we live and move in this tradition too—we know that we’re in for a conversation about freedom, and about covenant, and about what it means to be Israel (those who wrestle with God). Geography matters. In the wilderness, we are tested, provoked and challenged: “Repent!” he cries, “for the kingdom of God, the kin-dom of love, has come among you.” Repent, for the kin-dom of love has come among you. It’s time to embrace freedom—the kind of freedom that embraces sisterhood and brotherhood as gift and calling, the kind of freedom that lives in service to the common good, the kind of freedom that glorifies the God of heaven and earth.

This kind of repentance isn’t quick and easy, in and out of the booth before mass. This kind of repentance is a turning, a turning of our whole selves to new commitments and joys.

4.

So what happens out there—in the wilderness—is something like confession. It’s a dynamic and new beginning for Jesus, to be sure. It’s a luminous moment and a vocational turning point for Jesus and really for all of us who read along. But at the heart of it all is something like confession. John preaching repentance. All Israel wrestling with repentance and freedom. And Jesus joining them there, and seeking John out, for confession. And renewal. A turning of his whole self.

Now for many of us confession carries with it a fearsome kind of spirit and memory. We associate confession with these painful moments of wrong-doing and self-contempt: and with an obligation to come clean before God (or a priest or patriarch of some kind). We imagine dark booths in drafty churches where terrible things are confessed and then strangely absolved. And we remember old theological systems that have fueled self-hatred and despair. In some traditions, confession reduces the Christian life to bad choices, hierarchies of blessing and diminished spiritual creativity. But who needs all that? That kind of confession seems to reject the image of God in us and in our holy human spirit. That kind of confession motivates by fear, not love. And I see none of that in Jesus’ gospel, none of it. In fact, Jesus offers a consistent and persistent critique of just that kind of religion. He’s done with it.

So that’s not what this confessional moment is about. Here in the early scenes of Matthew’s story. This confessional moment is about two young people, maybe they’re cousins, maybe they’re soulmates, maybe just two visionaries with hope in their hearts. This confessional moment is about their finding one another in the wilderness, experiencing the call to freedom and repentance together, and then welcoming the baptismal spirit, the blessing of God in their lives. Together.

So the word: CONFESSION. For you wordsmiths out there. Con-fession. Two Latin words: Con, meaning together. Ferre, meaning to carry, to hold, to bear. In this confessional moment (con-ferre), Jesus seeks out John, that they might together bear this ancient hope, this dynamic and fragile prayer in their hearts. Does Jesus believe in a God who stirs in creation and dances in every breeze? Absolutely he does. Is Jesus a radically free soul? I think so, or he’s ready to be one. Is Jesus a practitioner of freedom and grace and holy chutzpah in a world of conflict and danger? I think that he is indeed. And that’s why he seeks out John. In the wilderness. He’s ready for this confessional moment . Where he and John bear together (con-ferre) the ancient hope, the dynamic prayer, the love they experience in their hearts.

5.

So let me suggest this. We too are called to confession. We too are called to bear this ancient hope together. The Spirit of God anoints us all, blesses us all, endows us all with freedom and compassion. And we live into that blessing together.

When you show up at a Portsmouth Pride Festival on a Saturday afternoon in October, and when you share a story there, of love without boundaries, and grace without exception, and a church without judgment—you are confessing a faith that heals and restores. You are bearing this hope together and imagining with them a world liberated from hatred, reconciled in love. A world we can all live in and care for and bless. And that my friends, that is the essence, the meaning, the practice of freedom. Freedom with God. Freedom for one another.

And when you pick up the phone to call a friend in need, a neighbor with cancer, or a parent whose child is overwhelmed by despair—when you make that call and offer yourself to another—you are confessing a faith that heals and restores. You are bearing this hope together and imagining a world stitched together by compassion, a world warmed by tenderness and touch, a world where you and I keep watch for one another. And that too—that is the essence, the meaning, the practice of freedom. Freedom with God. Freedom for one another.

And it won’t always to easy or without complication and conflict. Our wrestling will involve differences of opinion and sometimes even competing priorities. But there too, we look upon one another with lovingkindness and respect. Even in our disagreements, we recognize our shared faith, our shared love, our shared calling as the people of God in this place. And that is freedom. That stirs the power of God, the freedom of God in our hearts. We are free to listen carefully, to work bravely together, to disagree honestly, and to move forward in compromise, compassion and (yes) confession. Because, as we say, God is good. All the time!

What you need to know is this. We are here for you. You do not have to do this kind of confessing alone. We are here for one another. We come together to confess all the love in our spirits and all the pain in our hearts. That’s what church is. That’s what all this means. We go out to the wilderness together. We stand in the light together. We surrender to the river together.

And we receive over and again the blessing of God’s spirit. And we rejoice in the forever kindness of God’s peace. And we become the hands, and the feet of God’s mercy. Together. And that’s our confession. Every one of us, all of us, bathed in the light of God’s Spirit. And we become the hands, the feet, the manifestation of God’s mercy and freedom. Amen.