Sunday, February 27, 2022

Luke 9:28-36

1.

|

| Cruciform #1 (Polly Castor) |

When we’re reading scripture, we’re bringing to these ancient texts our hopes, hurts and (most importantly) our hermeneutics. There’s a word you don’t hear at the grocery story: hermeneutics. But they matter in the church. For example, if your hermeneutic is personal salvation, if you believe scripture exists to save your soul, then you’re going to read these gospel stories to decipher that truth: that singular path by which you might find comfort, reassurance and even salvation itself. That’s one hermeneutic. And it drives a lot of biblical study. And a lot of preaching in the church.

But the hermeneutic that seems to drive Luke—and it’s unfolding in the story this morning—the hermeneutic that seems to drive Luke is discipleship. Discipleship. Across the pages and parables of Luke’s gospel, Jesus is most committed to teaching a particular practice, and gathering a particular kind of people, and building a particular kind of community. If your hermeneutic is discipleship, you’re not sifting through the gospel for clues to your own salvation, for tips on avoiding your own destruction; you’re reading Luke’s story to encounter a teacher, a presence, a tradition of wisdom that seeks your transformation and growth. And I think I’ll amend that just a bit. If your hermeneutic is discipleship, you’re reading to encounter a teacher, a presence, a tradition of wisdom that seeks not just your transformation, but ours, the church’s, even the world’s.

Discipleship is a daily walk. It’s a lifelong journey. It’s not a 59 minute Sunday service. Or a 15 minute Sunday sermon. And it’s hardly a four-part formula for salvation either. Discipleship is a spiritual stirring, a human awakening and (most importantly) a shared project of prayer and persistence and resistance in a world at war with itself. And if you read Luke’s gospel as an invitation to discipleship, you find yourself drawn—with a cast of characters, by the way—you find yourself drawn into a strange, disruptive, but yes, a delightful movement. Prayer and persistence and resistance.

Yesterday in Portsmouth Bill McKibben spoke to a crowd of church folks about climate change, and the urgency of social and spiritual transformation in our time. To be honest, I’m not sure he mentioned Jesus even once—not by name—but he was talking for sure about discipleship. About the wisdom that transforms us into collaborators and revolutionaries. About the tradition that releases in us the power of love, blessing and nonviolence. He’s intense, Bill McKibben is, and he pulls no punches. But every time he speaks on climate change, he voices this disruptive call to discipleship. And it’s so much like Jesus. “We’re late enough in this game,” he says, "that you can’t make the math work one Prius at a time. So the most important thing an individual can do”—and again, this is Bill McKibben—“the most important thing an individual can do is be a little less of an individual, and join together with others in building movements, that allow us to really challenge the economic and political status quo.”

By the way, he said we have seven years and two months to get this right. On climate change. So discipleship, and movements, and the transformation of our lives and communities? Urgently.

2.

Which brings us to this somewhat surreal and quixotic story of Jesus’ transfiguration on Mount Tabor. And Jesus is praying up there on the mountain top, and everything about him shimmers in the light, and his clothing is brightened and whitened before them all. Now if your hermeneutic is personal salvation, you’re probably vibing with Peter when he says: “Hey! This is fantastic! We’ve got Moses and Elijah, and now we’ve got Jesus; let’s build three sanctuaries and breathe a sigh of satisfaction and relief.” This is the quintessential mountain top experience. And Peter’s a happy camper.

But if your hermeneutic is discipleship, if you’re answering Jesus’ call to mercy and service, if you’re reading with a ragtag community of lovers—then you’re asking other questions. And coming to grips with other possibilities. Discipleship means a very different reading strategy.

You see, on the front end of this story, just before Jesus takes Peter and James and John up that mountain, he’s been doing some pretty heavy teaching about love and mercy and the cost of discipleship. Tending to victims of war. Feeding thousands in the wilderness. Touching and healing untouchables in the street. Challenging the status quo.

And his ministry seems to coalesce now, around that extraordinary moment at Simon’s house—when an uninvited woman pushed through and anointed his feet with her tears and a jar of perfumed oil. That was last week’s story, right? To be anointed, Jesus seems now to believe, is to fear nothing and love everything. To be anointed is to serve, whatever the cost. You see, personal salvation isn’t the question. Love is the question. Commitment is the question. Discipleship is, for the church at least, always the question. Will we be transformed?

And about a week before their retreat on that mountain, Jesus has gathered the disciples for study, for reflection, for teaching. And I have to imagine that these sessions are lively conversations, bright with prayer and song, restless with hope and determination. He’s a rabbi, a teacher. And Jesus’s reminded them, again, that he’s risking everything for this gospel, that he’s facing a very uncertain future, and that suffering is indeed inevitable. For him and for them. As Bill McKibben told us yesterday, “there are really no guarantees as to how this is all going to go.”

And that morning, in that classroom, Jesus puts a pretty fine point on it: “If any want to become my followers,” he says, “let them deny themselves and take up their cross and follow me.” Love is the question. Commitment is the question. Discipleship is always the question. If any want to become my followers…To be anointed, after all, is to fear nothing and love everything.

So that’s what’s going on this morning, as we’re climbing this mountain with Jesus. If our hermeneutic is discipleship. Down below, the world’s at war. Wannabe emperors anxious to rebuild failed empires. Hoping to control oil supplies and consolidate wealth. Ruling with rage and intimidating with violence. Down below, despair is a pandemic. Children fearing for the planet. Democracies in disarray. On sale to the highest bidder.

There are no guarantees. But we’re drawn to this rabbi, to this teacher who believes in the promises of God, and makes us believe in those promises, and in the wonders of the earth, and in the practices of mercy and justice. We’re drawn to this rabbi, this teacher who embodies good news when he breaks bread at our tables and gathers the children with laughter and proclaims release to the incarcerated and captive. He will not give up on us, and he will not give up on broken hearts and occupied peoples anywhere. Not in Kyiv. Not in Gaza. Not the Strafford County Jail. Not anywhere. Because God is love, he says, and wherever two or three gather in God’s name, love reveals another way. Love brightens darkness and despair. Love says: “Come with me.”

3.

And it’s this invitation, this grace that stirs in our hearts as we climb together. Jesus reveals divinity in hopefulness, and power in compassion. It takes a little bit of courage to walk that way. No, check that, it takes a whole lot of courage to go where Jesus’s going. To believe, with Jesus, that the true power of the world, God’s power, is compassion and mercy and grace.

Because Putin’s armies are indeed mighty; and his mania is brutal and unfettered. And all this weaponry—all this sophisticated, bedazzling weaponry—is understandably scary and seemingly without equal. Just turn on CNN this afternoon. It takes a whole lot of courage to go where Jesus’s going. Without weapons. Without bluster. Without hatred in your heart. It takes a whole lot of courage.

But Love says: “Come with me.” Jesus says, “Pray with me.” Love is not easy, he says. Love is not without cost. But there is another way. It takes some faith. But there is another way. Let’s go together.

4.

Now Peter’s tempted—as I might be, as we all might be—to build a few sanctuaries on the mountain top, to stay for a long while and enjoy the company of saints and spirits, of hawks and foxes. And I think this gets to the heart of the story. Of course we want to protect ourselves. Of course we want to rest in the safety of the familiar, in the comforts of stories we’ve told for a very long time and identities that have suited us well. Discipleship, though, is risky business. On that journey, with Jesus and so many others, we expose ourselves to vulnerability and uncertainty. On that journey, we risk the privileges we’ve come to count on for the unnerving grace that sets us free. It's scary to take on climate change. It’s overwhelming to speak truth and love to empires built on violence and deception. But the only way to hope and healing is through the cross. That’s how Jesus sees it anyway. “If any want to become my followers, let them deny themselves and take up their cross and follow me.” And the voice in the cloud interrupts Peter’s reverie. The voice in cloud calls to us all. This is the Anointed One, it says. This is the Child of God. Fear nothing, love everything. Listen to him. Take up your cross and follow.

What we know, friends, as Jesus’ disciples, as Jesus’ kin, is this. Putin’s armies cannot and will not feed hungry, frightened children, or revive dispirited cities, or heal human hearts. We know this. And all that sophisticated weaponry, all that brute force: it cannot and will not inaugurate a jubilee of justice or a world of collaborative genius and peace. We know this too. And we know that reactionary politics, the meanspirited politics unleashed in our own land, in our own state even this winter—we know that this kind of cynicism offers no real future at all. Not in New Hampshire, and not in Washington or Moscow or anywhere else. Love says: “Come with me.” Love reveals another way. So we follow Jesus down the hillside, down the mountain, into the streets. To love our enemies. To save our planet. To offer our children the hope they need, and the future they deserve.

5.

It strikes me this morning that the point of this tradition—the gospel we read together, the hymns we sing together, the bread we break together—it strikes me that the point isn’t Christianity at all, but discipleship. A beloved community, collaborative in spirit, humble at heart, bold in prayer and action. We know that Jesus didn’t set out to split off a new religion; he didn’t intend to found anything like the Christian church. This was the farthest thing from his Jewish mind, from his prophetic heart. And he certainly never wanted his gospel to be used as a threat, as a judgment, as a means of separating saved souls from all the rest.

No, what we do together here is love, and pray, and build relationships of care and creativity. What we do together here is weep sometimes for all the war, and all the pain we inflict on another; and then we turn from all that violence and choose something different, something holy, something like mercy and justice. And then we take a loaf of bread—the beauty of the earth, the gift of its seasons—and we bless it, we remember our teacher as we bless it and break it, and we commit our lives and our energies and our futures to his. To be brave like Jesus. To be broken like Jesus. To be anointed, to be awakened, to be alive like Jesus.

Amen and Ashe.

But Love says: “Come with me.” Jesus says, “Pray with me.” Love is not easy, he says. Love is not without cost. But there is another way. It takes some faith. But there is another way. Let’s go together.

4.

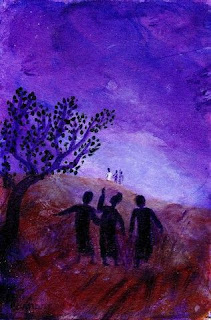

|

| "Transfiguration" (Bernadette Lopez) |

Now Peter’s tempted—as I might be, as we all might be—to build a few sanctuaries on the mountain top, to stay for a long while and enjoy the company of saints and spirits, of hawks and foxes. And I think this gets to the heart of the story. Of course we want to protect ourselves. Of course we want to rest in the safety of the familiar, in the comforts of stories we’ve told for a very long time and identities that have suited us well. Discipleship, though, is risky business. On that journey, with Jesus and so many others, we expose ourselves to vulnerability and uncertainty. On that journey, we risk the privileges we’ve come to count on for the unnerving grace that sets us free. It's scary to take on climate change. It’s overwhelming to speak truth and love to empires built on violence and deception. But the only way to hope and healing is through the cross. That’s how Jesus sees it anyway. “If any want to become my followers, let them deny themselves and take up their cross and follow me.” And the voice in the cloud interrupts Peter’s reverie. The voice in cloud calls to us all. This is the Anointed One, it says. This is the Child of God. Fear nothing, love everything. Listen to him. Take up your cross and follow.

What we know, friends, as Jesus’ disciples, as Jesus’ kin, is this. Putin’s armies cannot and will not feed hungry, frightened children, or revive dispirited cities, or heal human hearts. We know this. And all that sophisticated weaponry, all that brute force: it cannot and will not inaugurate a jubilee of justice or a world of collaborative genius and peace. We know this too. And we know that reactionary politics, the meanspirited politics unleashed in our own land, in our own state even this winter—we know that this kind of cynicism offers no real future at all. Not in New Hampshire, and not in Washington or Moscow or anywhere else. Love says: “Come with me.” Love reveals another way. So we follow Jesus down the hillside, down the mountain, into the streets. To love our enemies. To save our planet. To offer our children the hope they need, and the future they deserve.

5.

It strikes me this morning that the point of this tradition—the gospel we read together, the hymns we sing together, the bread we break together—it strikes me that the point isn’t Christianity at all, but discipleship. A beloved community, collaborative in spirit, humble at heart, bold in prayer and action. We know that Jesus didn’t set out to split off a new religion; he didn’t intend to found anything like the Christian church. This was the farthest thing from his Jewish mind, from his prophetic heart. And he certainly never wanted his gospel to be used as a threat, as a judgment, as a means of separating saved souls from all the rest.

No, what we do together here is love, and pray, and build relationships of care and creativity. What we do together here is weep sometimes for all the war, and all the pain we inflict on another; and then we turn from all that violence and choose something different, something holy, something like mercy and justice. And then we take a loaf of bread—the beauty of the earth, the gift of its seasons—and we bless it, we remember our teacher as we bless it and break it, and we commit our lives and our energies and our futures to his. To be brave like Jesus. To be broken like Jesus. To be anointed, to be awakened, to be alive like Jesus.

Amen and Ashe.